February is Black History Month, and its origins date back to the second week of February in particular. African-American scholar Dr. Carter G. Woodson founded what was then called “Negro History Week” in February 1926, which he selected to coincide with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. At that time, public schools did not teach Black history (nor any history of minority groups). African-American children did see their own culture and history reflected in the curriculum.

I read an excellent profile on Dr. Woodson in my hometown’s newspaper a few weeks ago. I had not realized he was born in Southside Virginia, and that he is the only person in the US with parents who were once enslaved to earn a Ph.D. in history. Dr. Woodson also founded the Association for the Study of African American Life and History and the Journal of African American History. He was truly the father of African American history in the United States.

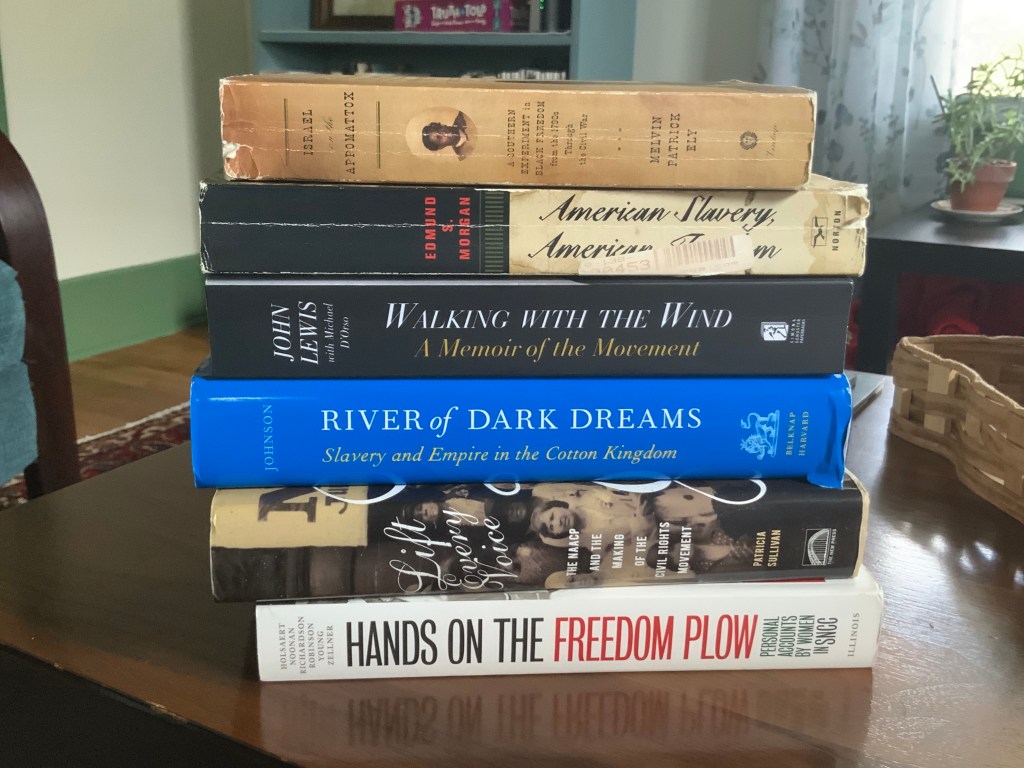

So in celebration of Black History Month and with it coming to a close, I wanted to give some book recommendations for family and friends so they can keep learning all year. These picks span several periods in American history and include some classics in the field. I’ve read each of these books (in undergrad and grad school). While these were written for academic audiences, I chose ones that I think speak well to a broader audience (although I could make many more recommendations!).

17th-mid-19th Century United States

Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia, 1975

While this book is from 1975, it still holds up well. It deals with a paradox in American history – how did Americans form a republic in a slave society? Edmund Morgan explores the history of the Virginia colony in the 17th century and forms of labor – indentured servitude and slavery. Morgan argues that after Bacon’s Rebellion (which was an uprising of poor whites and Black freedmen), Virginia colonists transferred class prejudices to race and then codified slavery based on race in the Virginia legal code. The book ends with an excellent question to ponder: “Is America still colonial Virginia writ large?”

Walter Johnson, River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom, 2013.

Walter Johnson is a historian at Harvard, and much of his work focuses on the lived experiences of enslaved people. His first book discusses the antebellum slave market, and this one examines the economic underpinnings of the institution of antebellum slavery. Johnson notes that slaveowners treated enslaved individuals as literal capital to build their cotton plantations since most of the cotton economy existed on credit. Of all of the books on this list, this one is probably the most “academic,” but he writes in a style that makes the narrative portions easy to follow

Deborah Gray White, Arn’t I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South, 1985 (revised edition 1999).

Between the 1950s and 1970s, several historians revisited the subject of slavery and rebutted racist stereotypes in the historical literature. Deborah Gray White was the first professional historian to write about the experiences of female slaves and rebutted the stereotypes of the “mammy” and “Jezebel.” She, Darlene Clark Hine, and Angela Davis created a foundation for the study of Black women’s history. Arn’t I a Woman? is one of the classics in this subgenre now.

Melvin Patrick Ely, Israel on the Appomattox: A Southern Experiment in Black Freedom from the 1790s through the Civil War, 2004.

I first read this book in college when I took Dr. Ely’s senior colloquium, “Freedom and Slavery in the Old South” in Fall 2010. Dr. Ely wrote about the free Black community, Israel Hill, outside of Farmville, Virginia. Israel Hill formed on land that originally belonged to Thomas Jefferson’s cousin, Richard Randolph, who held strong antislavery beliefs. When Randolph died relatively young, he freed the enslaved people on his plantation and gave them that land in his will. The founders of Israel Hill went on to form the First Baptist Church of Farmville, which was the birthplace of the Farmville civil rights movement (and one of the Brown v. Board of Education cases) over 100 years later. Ely discusses the complexities of freedom for this community, noting that while they were free, they faced discrimination and intense scrutiny from white people, too.

Mid-Late 19th Century: Reconstruction and Jim Crow:

W.E.B. DuBois, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880, 1935.

DuBois, a sociologist by training, wrote one of the first books that refuted the racist stereotypes about Black people in the Reconstruction era. In 1935, most of the historical literature on Reconstruction, often called the “Dunning School,” told the same narrative that D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of Nation told: Black people were incompetent leaders after slavery and white people needed to “redeem” the South, casting the Ku Klux Klan in a positive light. DuBois notes Black people were successful leaders, ushering in the 13th-15th Amendments to the Constitution and setting the nation on a more progressive path. He notes in the last chapter “The Propaganda of History” that the Dunning School had put forth three myths: (in his words) “All Negroes were ignorant,” “All Negroes were lazy, dishonest, and extravagant,” and “Negroes were responsible for bad government in Reconstruction.” DuBois notes that all of these myths were born of the authors’ biases rather than sound historical research. He implored the discipline to do better, and his words are still prescient for today:

“What is the object of writing the history of Reconstruction? Is it to wipe out the disgrace of a people which fought to make slaves of Negroes? Is it to show that the North had higher motives than freeing black men? Is it to prove that Negroes were black angels? No, it is simply to establish the Truth, on which Right in the future may be built. We shall never have a science of history until we have in our colleges men who regard the truth as more important than the defense of the white race, and who will not deliberately encourage students to gather thesis material in order to support a prejudice or buttress a lie.”

W.E.B DuBois, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880, pages 647-648.

Leon Litwack, Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow, 1998.

Litwack’s work focuses on the period after Reconstruction when racial oppression reached its height in the South. He explicitly discusses the violence that African Americans faced (lynching) and notes that the Black community built their own institutions as a refuge. These institutions, like churches and universities, allowed for flourishing in a time of severe oppression. His work on lynchings eventually became part of a traveling exhibit, “Without Sanctuary:” https://withoutsanctuary.org.

C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow, 1955.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. famously called this book the “historical bible of the civil rights movement.” This book grew from Woodward’s speech at the University of Virginia in 1954 (after the Brown decision), and he argues that Jim Crow segregation was not a natural outgrowth of slavery, Reconstruction, or even white redemption. It came from haphazard ideas from Southern whites in the 1890s, who adopted this system from the North. His argument, in the 1950s, was that segregation was not always the social and political norm of the South and that it could be reversed.

Twentieth Century/Civil Rights Movement

Patricia Sullivan, Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the Civil Rights Movement, 2009.

I would be remiss if I didn’t include my Ph.D. advisor’s work here. Dr. Sullivan traces the grassroots network formed through local NAACP chapters and field secretaries. People like Ella Baker, Amzie Moore, and Medgar Evers laid a foundation for the students of SNCC and CORE to build a new movement in the 1960s. She also traces the work of the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund and its legendary lawyers from Howard University and other HBCUs. Charles Hamilton Houston, Thurgood Marshall, Robert Carter, Spotswood Robinson, and others did the work on the legal side of the battle against Jim Crow, challenging segregation laws in many states across the US.

Cleveland Sellers, The River of No Return: The Autobiography of a Black Militant and the Life and Death of SNCC, 1990.

I had the immense privilege of meeting Dr. Sellers in the first year of my Ph.D. program. He was a member of SNCC and is most known nationally for being wrongfully arrested in the aftermath of the Orangeburg Massacre in February 1968. This memoir deals with that time and his experiences in Mississippi during the 1964 Freedom Summer. John Dittmer, whose book is listed below, called Dr. Seller’s book one of the most important books on the history of the civil rights movement.

Holsaert, Faith S, Martha Prescod Norman Noonan, Judy Richardson, Betty Garman Robinson, Jean Smith Young, and Dorothy M. Zellner, eds. Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, 2010.

My favorite works on the civil rights movement are first-person accounts from those who participated. This is a collection of personal accounts from women in SNCC, and while it’s 592 pages, the narrative these women tell is gripping. In all of the accounts, they note the danger and personal risks they faced as women, especially Black women, as they went into the Deep South. They also give an honest portrayal of the organization of SNCC, which suffered from internal conflict along racial and gender lines. Many of the women note the sexism they faced from members of the movement. I got to meet two of the editors while at USC, Martha Noonan and Judy Richardson, and I will not soon forget those conversations.

John Lewis (with Michael D’Orso), Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement, 1998.

Many people have a personal hero, and John Lewis is one of mine. I first heard of him in college, in Dr. Ely’s African American History class, and I began reading about his life and work in the movement. He risked his education, reputation, and life so many times; to me, he is the epitome of courage. His memoir details his rural upbringing in Alabama and his activism as a college student in Nashville through his political career.

John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi, 1994.

This book won the Bancroft Prize in History, and it was one of the first books on the civil rights movement to recognize the importance of local, grassroots activism in ending Jim Crow segregation rather than national figures or the federal government. He focuses on Mississippi activists, including Fannie Lou Hamer and Amzie Moore, who previously had not been heralded for their civil rights activism. Dittmer’s work set off a new wave of scholarship on local civil rights movements; my research and dissertation fall into that wave but at an even more local level.

Brenda E. Stevenson, The Contested Murder of Latasha Harlins: Justice, Gender, and the Origins of the LA Riots, 2013.

Since I was born in 1990, I did not have much awareness of the LA riots as a child or teenager. I learned more about Rodney King and what happened in LA as an adult. I do think that up until recently, the story of Latasha Harlins got lost in the narrative. She was an unarmed, 15-year girl who was shot in the back by a Korean shopowner after a scuffle over perceived shoplifting in 1991. This incident strained relations between the Korean and Black communities of Los Angeles, and while the shopkeeper was convicted of voluntary manslaughter, the judge and California Court of Appeals upheld a sentence of no jail time, causing relations between the communities to deteriorate even further. The Court of Appeals ruling on the sentence came one week before the not-guilty verdict of the police officers who were charged with excessive force in the arrest and assault of Rodney King. Stevenson’s book details Harlins’s story along with background information about the development of the Black and Korean communities of Los Angeles. I read this book in 2017, which was the 25th anniversary of the riots. Several media outlets did retrospectives, and it was encouraging to see more people recognize how complicated the racial environment of Los Angeles was, even in the 1990s.

What’s on my Black history reading list for this year? First up for sure is Invisible No More: The African American Experience at the University of South Carolina, edited by Robert Greene II and Tyler D. Parry, both alums of my department. Monica White’s Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement has been on my list for some time now as I’ve been interested in the intersection of tobacco production and the civil rights movement as part of my research. Finally, I want to read through two books from USC faculty. Dr. Sullivan’s new book on Robert Kennedy, Justice Rising: Robert Kennedy’s America in Black and White. Her focus is on RFK’s role in the movement as US Attorney General. Woody Holton, who is also at USC, just released a new book called Liberty is Sweet: The Hidden History of the American Revolution. He explores how marginalized groups like African Americans, women, and Native Americans influenced the Founding Fathers’ actions in the Revolution. I’ll be reading these throughout 2022 (and get to take my time with them!), and I’ll report back on how I liked them.