Today’s post marks the first of a series adapted from my public history MA thesis and Ph.D. dissertation on the history of the civil rights movement in Southside Virginia. Sixty-two years ago today, sixteen Black high school students challenged segregation at what was then known as the Confederate Memorial Library (now the Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History) in Danville, Virginia. Part 1 tells the story of the sit-in; part 2 (to be published next week) tells the context of Confederate memorialization surrounding the library and why that mattered in the struggle for civil rights.

On April 2, 1960, when sixteen African American students walked up the front steps of the white-only branch of the Danville Public Library, many thoughts must have been racing through their minds. Maybe they reflected on the atmosphere of the tobacco and textile-dominated city of Danville, Virginia, and what the potential repercussions of their actions could be. Jim Crow segregation seemed nearly impenetrable in the city. Schools, public facilities, churches, employment, and recreational areas were all segregated. Most of the African American community worked in low-income jobs in the tobacco warehouses or factories or lower rank jobs at the textile mills. As young African Americans, opportunities for their futures looked disheartening.

Maybe though, the students recognized glimmers of hope. There was a small Black professional class in Danville that headed up the community through churches and a branch of the NAACP with a well-established youth chapter. Forty-five miles to the south of Danville, North Carolina A&T University students had set off a broad, grassroots movement by sitting in at the lunch counter at the Greensboro, North Carolina, Woolworth’s earlier in February. Maybe these Danville students had friends or relatives who participated in the sit-ins by Hampton University, Virginia Union University, and Virginia State University students across the Commonwealth. Maybe they thought of the students ninety miles away in Prince Edward County who were denied their education by the county school board who had shut down all public schools in 1959 rather than integrate them after the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954. Maybe they took some inspiration from the students who started the student movement in Virginia by walking out of Farmville’s Moton High School in 1951. Maybe they worried that they would face similar repercussions because active massive resistance groups were operating in Danville at that time.

Surely though, the thought that weighed the most on their minds was that they were about to take a stand and make a statement about history and public memory. The day they walked into the Danville Public Library at the Sutherlin Mansion was the ninety-fifth anniversary of Jefferson Davis’s arrival in the city and the beginning of his stay at that very building. The Danville Public Library occupied an antebellum mansion that the local United Daughters of the Confederacy and Sons of Confederate Veterans dubbed the “Last Capitol of the Confederacy.” The library at that time was the best-preserved and most revered relic from the Civil War in Danville. By asserting their presence in the library, these students were not only challenging the Jim Crow laws of the city but also the cultural dominance of the “Lost Cause of the Confederacy” in Danville. Predictably, the city closed the library immediately, but this sit-in became an instigating event for a larger local civil rights movement that developed over the next three years, peaking in 1963. For decades, the Sutherlin Mansion represented history as a weapon of white supremacy, and the sit-in fundamentally challenged it. The refusal to integrate the library and to be the last segregated library in the state represented Danville’s white elite’s dogged commitment to Jim Crow segregation.

Likewise, the racial struggles of the post-Reconstruction, Readjuster period still resonated almost a century later in local politics but also the social dynamics of Danville. The 1883 Danville Massacre that left four Black men dead foreshadowed the same tension over the issue of integrating the public library in 1960. A large part of the backlash to the integration of the library was grounded in the Confederate memory of the space, institutionalized by the women of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Virginia has a long tradition of glorifying the Civil War and the Confederacy. It dominated white culture (and thus mainstream culture) during the Civil Rights era.

Forty years later, one of the Danville students who participated in the library sit-in, Robert Williams, recalled in an interview that the sit-in movement that began in Greensboro in 1960 lit a fire in the hearts and minds of Danville high school students: “That [the Woolworth’s sit-ins], of course, affected most Black youth across the country. We began to discuss what we could do in Danville.”1

These students’ discussions and plans kickstarted the grassroots civil rights efforts in the city. The momentum behind the civil rights struggle in Danville was the enthusiasm and hope of local Black students, who sought to bring change to the city beginning in 1960. They gained support from local chapters of the NAACP and SCLC and won some legal battles initially, but they encountered more resistance as their movement grew over the year, as was the case for most student-led movements across the South, sparked by the sit-ins of the spring of 1960.

As mentioned, the Danville students took inspiration from the sit-ins in Greensboro, North Carolina (less than an hour away from Danville), and in Petersburg, Virginia. On February 1, 1960, four North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College (NC A&T) students staged the first “sit-in” of the 1960s at Woolworth’s lunch counter. The four male students hatched the plan to ask for service at the lunch counter and then planned to sit on the stools at the counter until they were served or forcibly removed. By the end of the week, over three hundred students had joined them in “sitting-in.” African American students at historically Black colleges and universities across the South caught inspiration from the Greensboro students and began their own protests at lunch counters in towns and cities. By April of 1960, there had been over sixty sit-ins across the South.2

Danville’s local high school students tapped into this fervor when planning their own protest against Jim Crow segregation. The Danville students also took note of another nearby sit-in against segregated libraries unfolding in Petersburg, Virginia. Rev. Wyatt T. Walker, who later became a staff member of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, entered the segregated Petersburg City Library and requested Douglas Southall Freeman’s biography of Robert E. Lee in 1959. The library refused Wyatt, and the local chapter of the NAACP (of which Wyatt was president) petitioned the city council to integrate the library. The matter stalled for almost a year until late February 1960 when Petersburg’s Black students began attempting sit-ins at the library following unsuccessful sit-ins at the local lunch counters. On February 27, groups of young students (totaling over 140) entered the Petersburg Library, resulting in the city manager immediately closing the library. Petersburg’s Black community continued to fight a battle to desegregate the library for the rest of 1960.3

The organizers of the first protests in 1960 in Danville were older high school students. They included Chalmers Mebane, who became involved with NAACP meetings after school, and Williams, who was a member of the NAACP Youth Division and son of an NAACP lawyer. Mebane was also a veteran of the armed forces and twenty-three at the time of the sit-in although he had returned to school to finish his high school education. Mebane and others wanted to protest segregated lunch counters like the other sit-in demonstrations, but Williams pushed them to take on public services and amenities due to the NAACP’s influence in his life and understanding of the precedent set by the 1954 Brown decision. He knew they had a greater chance of success by attempting to integrate a publicly-funded space.4

Williams had also followed the news out of Petersburg and the struggle to desegregate the public facility there. The other youth followed Williams’s lead and decided to take on Ballou Park, an all-white public park, and the Danville Public Library, also known as the Confederate Memorial Library, located in the Sutherlin Mansion. There was an African-American branch of the library, but it only had three rooms compared to the mansion that housed the white branch; the branches were separate and unequal. The Danville Public Library was the last segregated public library in Virginia at this point. By the time the city created the Danville Public Library in 1928, Southern libraries had begun creating separate (yet unequal branches). The Danville Library created an African American branch in 1950 “at the request of Negroes.”5

The students conducted many planning meetings and welcomed adult leaders into their planning, including the then-current president of the local NAACP chapter, Rev. Doyle J. Thomas, Sr., minister of Loyal Baptist Church. Many of their meetings discussed the legal ramifications of their plans and what assistance they could receive from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund if they decided to take this issue to court.

The first sit-in took place on April 2, 1960, which was the ninety-fifth anniversary of Jefferson Davis’s flight from the city of Richmond at the end of the Civil War. The students began at Ballou Park on the western, more affluent end of Danville’s Main Street, anticipating that the city police would close the park, which they did. There were no arrests, but the students felt sure that provisions had been made if they needed bail money. They continued to the white branch of the library, the Confederate Memorial Library, located on Main Street. After going in and requesting to check out books, the librarian informed the group that the library was closed. The students sat down briefly but then left after they realized they would not be served. The next day, April 3, Danville City Council held an emergency session and passed an ordinance to limit the Confederate Memorial Library’s use to its cardholders only. The following week, the library and the park were closed to everyone, which the students counted as a victory.6

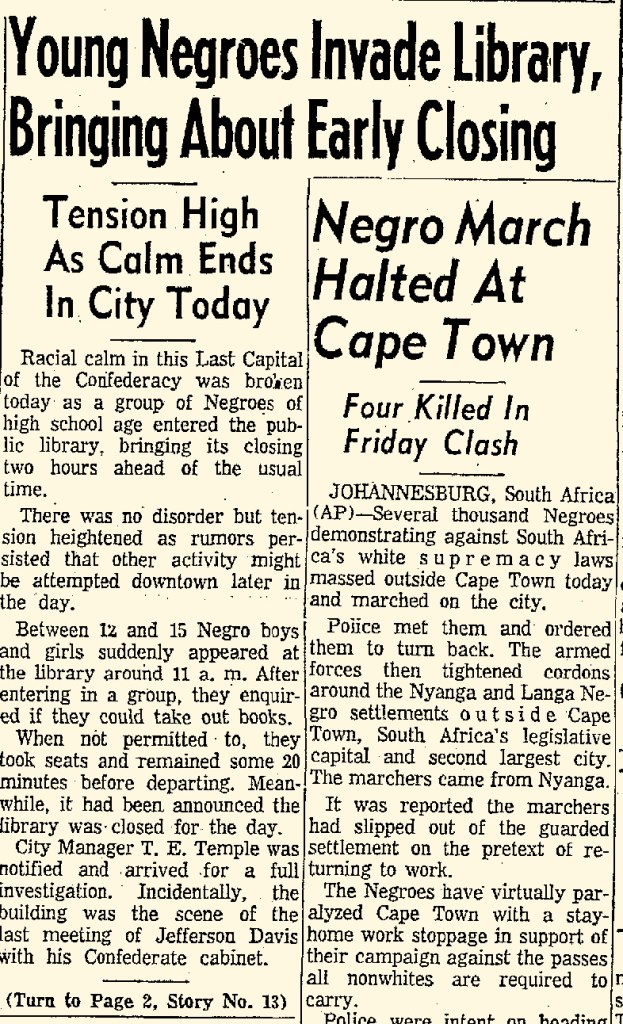

The Danville Register, a white-run newspaper, published an editorial that condemned the students. The editors of the Register also complained that the students entered the library on the anniversary of Jefferson Davis’s arrival in the city and his occupation of the Sutherlin Mansion and use of it as an executive mansion. The editors saw the students’ sit-in as “an invasion of the Confederate Memorial Mansion,” and then accused the students of breaking the “racial calm” that had existed in the city since November 1883 (referring to the year of the Danville Massacre that left four Black men dead).7

In the following week, the Black students and the NAACP experienced retaliation for their actions. On the night of April 9, crosses burned on the front lawns of Loyal Baptist Church and Rev. Doyle J. Thomas’s house. The next day, one of the local papers published the names and addresses of the students who were involved in the sit-ins, despite the participants being juveniles. However, the Black community of Danville was committed to this fight; a mass meeting at Loyal Baptist Church that evening drew over 350 attendees. On April 11, the city escalated the sit-in case to a full-blown legal struggle by voting to close the library rather than integrate. Two days later on April 13, the NAACP sought a federal injunction against all segregated public facilities in Danville. The plaintiffs in the case were Chalmers Mebane, Gladys Giles, Wayne Louis Dallas, Robert Williams, and Jerry Williams, all students who participated in the sit-in.8

On May 5, local federal judge Roby Thompson heard arguments in the case that the NAACP had filed against the city. Judge Thompson ruled in the favor of the plaintiffs and ordered that the library be open to African Americans but delayed the implementation of the injunction until May 20 to give the city time to appeal to a higher court. While the students and African American community jubilantly celebrated their court victory, the white citizens of Danville scrambled to devise a solution that would keep the Confederate Memorial Library white-only.9

As the summer of 1960 progressed, the white citizens of Danville dug in their heels at every turn in complying with the court order, including openly defying the judge’s injunction, holding a city-wide referendum on the status of the library, and eventually removing all tables and chairs from the library when forced to reopen. Before Judge Thompson’s injunction to integrate the library went into effect, a local judge set a date for a city-wide referendum where Danville voters would decide if the city would continue to have a public library; the referendum was set for June 14. On May 19, the Danville city council made a last-minute attempt to stop the injunction by voting to close all Danville libraries and bookmobiles. The Danville Bee reported that “word of the closing action spread rapidly during the afternoon and there was a rush on the main library last evening by persons desiring books, many of them getting stacks of volumes ranging up to between 15 and 20 in some instances.” The following day, all public libraries in the city were closed.10

As the referendum vote drew closer, there was an outpouring of criticism from across the state, yet local Danville citizens remained divided on the issue. William Faulkner condemned Danville and Petersburg in his commencement address at the University of Virginia; the Richmond Times-Dispatch also criticized Danville in an editorial, noting that libraries across Virginia integrated successfully. Competing white interests in Danville also fought to sway public opinion on the matter. The Committee for the Public Library, made up of white Danville citizens who wanted to see the libraries remain open, sent mailers to voters, as did the Danville Library Foundation, which formed to create a private, white-only library.11

June 14 not only brought a historic turnout but also cemented white Danvillites’ commitment to segregation and preservation of white supremacy and the Lost Cause of the Confederacy. Overwhelmingly, Danville’s white citizens voted for the library to remain closed. In response to the referendum, the Danville Bee published an editorial trumpeting victory for the white segregationists of the city with many references to the Confederacy and Danville’s history in the Confederacy. Their interpretation of the overwhelming vote to close the library was that the majority of Danville citizens wanted to hold firmly to Jim Crow and that the NAACP and the federal judiciary were akin to the federal troops of the Civil War:

“But the library issue does not end the matter because we shall soon find the NAACP seeking to retrieve its lost prestige in Danville and will be advancing again with a new approach. The ramparts must still be watched. The solidarity of Danville in this matter may have caused some acid remarks by the neo-liberals in coalition with the Negro voters, but it has at least reflected the truth that there are still a lot of unreconstructed rebels in Virginia not disposed to accept lightly an invasion of state rights by the federal judiciary, not the vindictive purpose of alien reformers who hoped by the referendum, to trumpet the claim that the onetime seat of the Confederate government had struck its colors…”12

“Vox Populi,” Editorial from the Danville Bee, June 15, 1960.

With many of Danville’s white citizens thinking the matter resolved, Danville’s city officials recognized that the NAACP suit against the city still stood; thus, they sought a solution that would require the smallest number of interactions between whites and African Americans. Throughout the summer, city officials created a plan of “vertical integration,” meaning that the library would be open to both races, but it would be open for “check-out only,” allowing for little social contact between the races. Ultimately, the persistence of the local NAACP and its lawyers would make the city fully integrate the library in December 1960, but Danville officials did their best to slow the process with the vertical integration plan and trial periods of integrated use.13

While the sit-in at the library was part of the wave of mass student sit-ins that spread across the South in the spring of 1960, this sit-in also challenged norms dictated by the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, too.

- Robert A. Williams, Danville Stories: Segregation to Civil Rights, interview by Emma C. Edmunds, Gladys Hairston, and Laurie Ripper, March 25, 2008, Virginia Center for Digital History, Charlottesville, Virginia, http://www.vcdh.virginia.edu/cslk/danville/bio_williams.html.

- Iwan W. Morgan and Philip Davies, From Sit-Ins to SNCC: The Student Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s (University Press of Florida, 2012); “Sit-Ins in Greensboro,” SNCC Digital Gateway (blog), accessed January 16, 2020, https://snccdigital.org/events/sit-ins-greensboro/.

- Wayne A. Wiegand and Shirley A. Wiegand, The Desegregation of Public Libraries in the Jim Crow South: Civil Rights and Local Activism(Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2018), 83.

- “City to Fight Library Suit Before Court,” Danville Bee, April 14, 1960, 2; Williams, Danville Stories: Segregation to Civil Rights.

- Wiegand and Wiegand, The Desegregation of Public Libraries in the Jim Crow South, 90-91.

- Wiegand and Wiegand, 91.

- “Legality Clashes with Reality,” The Register, April 3, 1960, Danville Stories: Segregation to Civil Rights, Virginia Center for Digital History, Charlottesville, Virginia, http://www.vcdh.virginia.edu/cslk/danville/legality_clashes.html.

- “City to Fight Library Suit Before Court.”

- “Council Faces Library Decisions After City Loses Round in Court,” Danville Bee, May 6, 1960; Wiegand and Wiegand, The Desegregation of Public Libraries in the Jim Crow South, 92.

- “Article Number 6,” Danville Bee, May 20, 1960. Wiegand and Wiegand, The Desegregation of Public Libraries in the Jim Crow South, 94.

- Wiegand and Wiegand, 95.

- “‘Pink Ballots’ Back-Firing on Advocates: Five Candidates Did Not Permit Use of Names on Negro Ticket,” Danville Bee, June 14, 1960; “Record Vote Being Cast in City Today: Totals Run Above Average,” Danville Bee, June 14, 1960; “Vox Populi,” Editorial from the Danville Bee, June 15, 1960.

- Wiegand and Wiegand, The Desegregation of Public Libraries in the Jim Crow South, 96.