This is part two of a post on the 1960 Danville, Virginia, library sit-in. See part one here. This post traces how Confederate memory in Danville played a large role in suppressing civil rights in the city.

Image: Young, Cassye. “The Memorial Mansion as Jefferson Davis Saw It.” Pamphlet. Danville, VA, 1955. Small Special Collection, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA.

Throughout the fight to integrate the public library in 1960, Danville’s white-controlled media and city officials kept referring to the sit-in as a breach of racial calm that had existed since the nineteenth century; racial calm in their minds meant the presence of cultural norms and laws regarding segregation. The implementation of segregation and institutional disenfranchisement in Danville began with an incident in 1883 involving street etiquette that left four men, white and Black, dead. Known as the “Danville Riot” to white citizens, this event according to Danville’s white citizens set race relations between white and Black citizens in their proper place, but to Danville’s African Americans, it ended any hope they had for being full participants in politics and society for nearly seventy years.

This riot precipitated African Americans losing political offices across the state. The Danville massacre was the beginning of Virginia’s redemption – white conservatives’ takeover of politics and society to disenfranchise and exclude African Americans from public life. Eventually, this disagreement over acceptable behavior in public spaces gave way to Jim Crow laws – “public behavior [was] a zero-sum game where one person’s gain was another’s clear loss.”1

In this atmosphere, white citizens began institutionalizing and formally preserving Confederate memory and the Lost Cause. Across the South, government and other institutions used the preservation of Confederate memorials to further buttress Jim Crow segregation.

In Danville, the Ladies Memorial Association was founded in 1872 and became a forerunner of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which organized in 1896. The Ladies Memorial Association was active in preserving Confederate memory at the time of the Danville Massacre; the group placed a Confederate Soldiers Monument in the Green Hill Cemetery in September of 1878. When the UDC chapter officially organized, they turned their attention specifically to the preservation of the “Last Capitol of the Confederacy” – the Sutherlin Mansion.

The current chapter of the UDC in Danville, the Anne Eliza Johns chapter, keeps a website and a list of their past projects. Their proudest accomplishment was saving the “Last Capitol of the Confederacy” by raising $20,000 (over half a million dollars today). According to the UDC, The Daughters were successful in their bid to save the mansion. They raised $20,000, and the City of Danville matched their contribution. In return, the city deeded two rooms in the mansion where Jefferson Davis slept and signed declarations for use as clubrooms. For the remainder of the twentieth century, the city retained ownership of the mansion save for those two rooms.2

In the 1920s, when the city began plans to build a public library (white-only), there was controversy on how to use the former Sutherlin property. As the idea of the Sutherlin mansion becoming a public building was being debated, the city considered charging rent for all the groups that wanted to use the building. That suggestion sparked an outcry from the Daughters as well as the broader community, who argued that the city would be reneging on the property deed that the Daughters would have use of the two clubrooms in perpetuity. The city backed down, but later in 1923, controversy arose again when deciding how to use the Sutherlin Mansion property as a public library. The city had received a large gift of money to build a library and was making a plan to build a new structure on the Sutherlin property. This prompted greater outrage from the Confederate groups. Speaking at a city council meeting, the presidents of the “Danville” chapter, the “Anne Eliza Johns” chapter, the Ladies’ Memorial Association, and the Sons of Confederate Veterans all decried any action that would alter, impede the view, or diminish in any way the mansion. All of these Confederate defenders painted this issue as a moral one, claiming the mansion property was “semi-sacred and that the building of the library there would be a ‘crime.’”3

Harry Wooding, Jr., the leader of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, (and also the son of prominent Danville mayor, Harry Wooding, Sr.) stated that “the library would destroy the sentiment and beauty of a place that the council was under a moral obligation to maintain the historic atmosphere and that if it came to a choice to putting the library there and doing without a library at all, he would rather see the present property remain intact…” Both chapters of the UDC released a joint statement to the press that advocated for a library but not in a way that would mar the Sutherlin Mansion in any shape or form.4

Ultimately, the city decided to place the library inside the mansion, yet the Daughters had to approve all changes to the structure of the building. There were several major structural changes done to the first floor to make the residential mansion suitable for a library. The Danville Public Library opened in 1928 and held several names, including the “Confederate Memorial Mansion,” “Confederate Memorial Library,” as well as the “Last Capitol of the Confederacy,” which it was “officially” dubbed in 1939 when the Daughters erected a marker in front of the mansion even though there was raging debate if it truly was the last Capitol.5

Within decades, it was evident that the preservation of the mansion and its use by the Daughters was grounded in memory, not history, as well as white supremacy. Memory is a murky term that is not easy to define, but it has much power in shaping and creating identity. Often conflated with “history,” public memory is distinctive because it tends to be something that is owned by a group, is sacred with absolute meaning that is emotional, is used by groups for creating identity, and coalesces in objects and monuments. As defined by David Blight, history is the “reasoned reconstructions of the past rooted in research,” and is secular, shared by everyone, often revised, and has an intellectual tone. How the Daughters spoke of the Sutherlin Mansion in their preservation efforts reveals an emotional tone and a view of anything Confederate as sacred. The action of the Daughters in Danville and across the South pushed for a narrative that vindicated the white redemption of the South and less so remembrance of the war.6

While the Danville Daughters had made the Confederate culture surrounding the public library seemingly impenetrable, the 1960 sit-in by the students shocked Danville’s white community. They saw it as not only an affront to the ordained social order but also termed it “an invasion” of the Confederate Memorial Mansion. By asserting their presence in the all-white library that also served as a shrine to the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, the students made a statement that they, too, should have a voice in how the history of this shared civic space should be told.

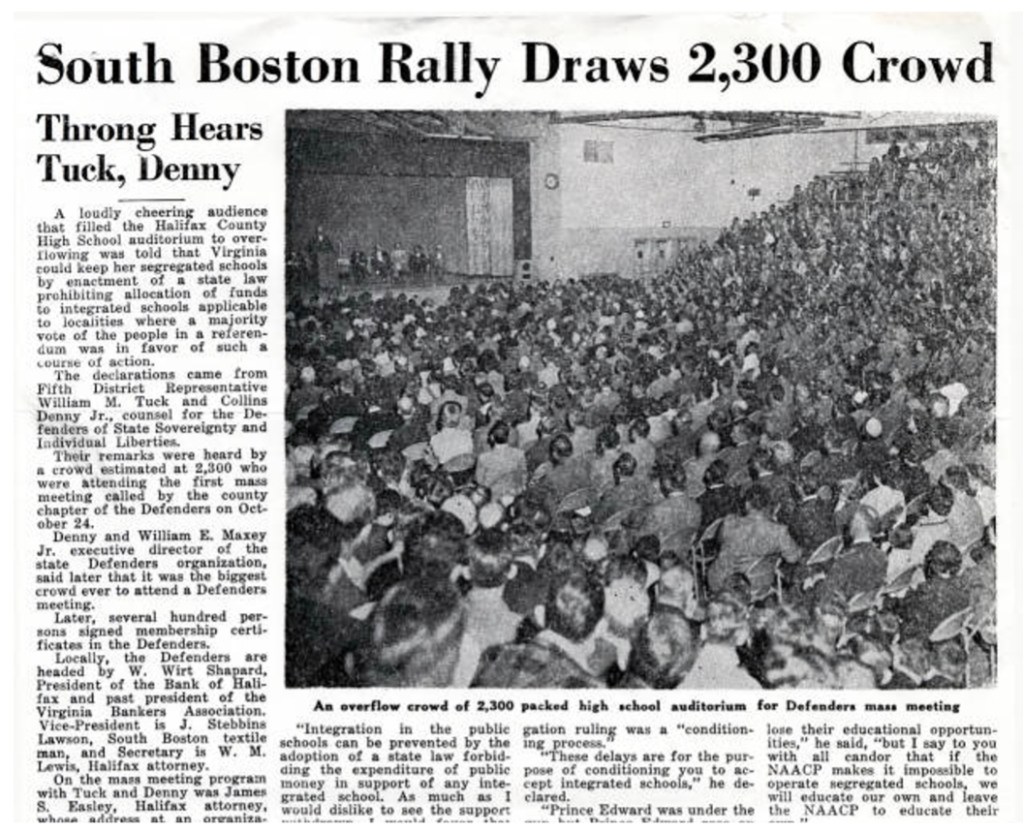

In Spring 1960, as the civil rights movement was heating up and as Congress considered civil rights legislation, Southside and Virginia politicians had a vested interest in keeping the Memorial Mansion sacred as the Civil War centennial was quickly approaching. Virginia’s senior senator, Harry F. Byrd, was the most prominent Virginia spokesmen against civil rights, and five days after the students sat-in, he released a statement denouncing the civil rights bill the Senate had just passed, calling it “a determined effort to enact punitive legislation, most of which was unconstitutional and punitive to the South.” One of his key members in the Byrd political machine was William M. “Bill” Tuck, who was the Southside representative in the House. Tuck saw this as an opportunity to fight against civil rights with commemoration. His motivations are clearly reflected in how Danville and Southside Virginians prepared for and celebrated the Civil War centennial. For these Virginians, the centennial represented the opportunity to reinforce the cause of Jim Crow in propping up massive resistance to integration.7

Bill Tuck of South Boston (originally of Buckshoal Farm) also happened to be the most prominent Southsider involved in the Civil War centennial on a national level. A member of the Byrd Democratic machine, Tuck’s career in politics became synonymous with conservatism, anti-communism, and states’ rights. Supportive of Strom Thurmond’s 1948 Dixiecrat campaign and a founding member of the Defenders of State Sovereignty and Individual Liberties, Bill Tuck also was one of several congressmen to lobby heavily for a national Civil War centennial. His bill to create a national Civil War centennial commission passed Congress in 1957. President Eisenhower signed it into law in September 1957. Two weeks later when Eisenhower sent federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas to enforce court-ordered school desegregation, Tuck criticized Eisenhower. At the same time, Tuck revealed what his intentions for the centennial were: “It [the centennial] could only serve to solidify our people in opposition to the Court decision and the tyranny to which we are now being subjected.” 8

Tuck’s sentiments expressed themselves in the name of the anti-integration group he helped form at the beginning of the massive resistance period, the Defenders of State Sovereignty and Individual Liberties. The Defenders’ main purpose was to prevent the integration of schools in Virginia, but they shared the values and operated similarly to the White Citizens Councils of the Deep South. There were many active chapters across Southside Virginia, including one in Danville. Tuck saw how the evocation of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy could bolster massive resistance feelings and sentiment in rural Southside Virginia.9

Tuck and other like-minded segregationists in Virginia formed a state commission to celebrate the centennial. The commonwealth appropriated 1.75 million dollars for its commission. Bill Tuck and segregationist newspaper editor James Kilpatrick agreed that the national and state commissions should be stacked with individuals who agreed with Tuck’s interpretation of the “War Between the States” and that one of the centennial’s main purposes was to defend the cause of states’ rights and massive resistance.10

Virginia politicians and their mouthpieces saw a clear correlation between celebrating and defending the Lost Cause as a major line of defense against federal civil rights legislation and directives. This played out at the Sutherlin Mansion in 1965 when the city hosted the celebration of Jefferson Davis’s arrival to Danville. The celebration included a parade, reenactments, dances, and commemorative speeches. In one of these speeches, Virginia’s Senator A. Willis Robertson compared the South’s opposition to the Voting Rights Act to “states’ rights” struggles in the nineteenth century. Robertson, along with Tuck, state delegate Dan Daniel, state senator Landon Wyatt, and the Virginia attorney general Robert Button, dressed up as Confederate officers and posed at the Confederate Memorial Mansion during the celebration. The local chapters of the NAACP and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference issued statements denouncing the celebrations, as they were blatantly white supremacist. However, by 1965, the last commemorations of the Civil War were coming to a close, and many Southern politicians recognized that the particular weapon of public memory was not proving effective to stem the tide of integration.11

Although Danville had finally integrated its public library by 1965, the city’s white citizenry remained committed to preserving the narratives of white supremacy. The attitudes apparent in Danville’s white citizens in 1883 still lingered in 1965. Black presence in public space and public narratives were still unwelcome among Danville’s white citizens. In the city’s struggle to stop the “Last Capitol of the Confederacy” from integrating, they believed they might have an effective weapon in the Lost Cause to preserve Jim Crow segregation. It had certainly worked in the earlier part of the century to use the Danville Massacre as an example of what would happen if African Americans were allowed to participate as full citizens politically and socially, and Danville’s white elite did an excellent job in enshrining the city with Confederate memory. However, that Confederate memory lost much of its power by the 1960s – it was no match for the Fourteenth Amendment, Civil Rights Acts of 1964, Voting Rights Acts of 1965, and the local, grassroots social movement brought to Danville by African American young people.

Robert Williams, one of the students who helped integrate the Last Capitol of the Confederacy, noted in an interview that he does not have specific recollections about that day, but he did note that the students were absolutely aware of what they were doing: “the main library building was a seminal place and had a great deal of significance… we felt on that day, very, very triumphant – that we had accomplished what we wanted – that was that if we could not use the park and the library, then they would be closed to all.” Of course, a struggle followed to fully integrate the library, but it also served to propel the formation of more civil rights organizing in Danville, which would grow over the next several years and culminate with a mass demonstration in the summer of 1963, as violence in Birmingham ignited protests in cities and towns across the country. By cracking the Virginia way of race relations in 1960, students had helped set the stage for the broader movement in Danville that exploded in 1963.12

- Jane Dailey, Before Jim Crow, 125.

- Anne Eliza Johns Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, “About The Chapter,” accessed September 20, 2016, http://www.aejohnsudc.com/index_files/Page400.htm; “Memorial Mansion Movement History,” Danville Bee, January 20, 1922; United Daughters of the Confederacy, “Minutes of the Eighteenth Annual Convention of the Virginia Division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy” (Richmond, VA, 1913), 115, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x001478621&view=1up&seq=7.

- “Realization of Free Public Library Is In Doubt – Deadlock Reached,” Danville Bee, May 31, 1923; “U.D.C. Chapters Make Clear Views On Library Question,” Danville Bee, July 24, 1923.

- “Realization of Free Public Library Is In Doubt – Deadlock Reached,” Danville Bee, May 31, 1923.

- Edward P. Alexander, “National Register of Historic Properties Nomination Form – Danville Public Library,” National Register of Historic Properties Nomination (Danville, VA: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, May 13, 1969); “Memorial Marker Is Unveiled,” Danville Bee, December 18, 1939.

- Cox, Karen L. Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture. 2019 edition with new preface. New Perspectives on the History of the South. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2019; Blight, David W. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Harry F. Byrd, “Statement by Senator Harry F. Byrd (D, VA) for release immediately upon passage of the Civil Rights Bill in the Senate,” April 7, 1960, Papers of Harry F. Byrd, Small Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Virginia.

- Robert J. Cook, Troubled Commemoration: The American Civil War Centennial, 1961–1965 (LSU Press, 2011), 30.

- “Report from the Defenders of State Sovereignty and Individual Liberties,” September 30, 1957, Norfolk Public Schools Desegregation Papers (1922-2008), Special Collections and University Archives, Old Dominion University Perry Library, Norfolk, Virginia.

- Cook, 32; “Letter from James J. Geary to James J. Kilpatrick,” May 4, 1959, James J. Kilpatrick Papers, Small Special Collections, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA.

- “Photograph of A. Willis Robertson, Dan Daniel, William Tuck, Landon Wyatt, and Robert Button,” Danville Register, April 2, 1965.

- Robert A. Williams, Danville Stories: Segregation to Civil Rights, interview by Emma C. Edmunds, Gladys Hairston, and Laurie Ripper, March 25, 2008, Virginia Center for Digital History, Charlottesville, Virginia, http://www.vcdh.virginia.edu/cslk/danville/bio_williams.html.